Late Hepatic Recurrence From Granulosa Cell Tumor: A Case Report

Granulosa cell tumors exhibit late recurrence and rare hepatic metastasis, emphasizing the need for lifelong surveillance in affected patients.

Introduction

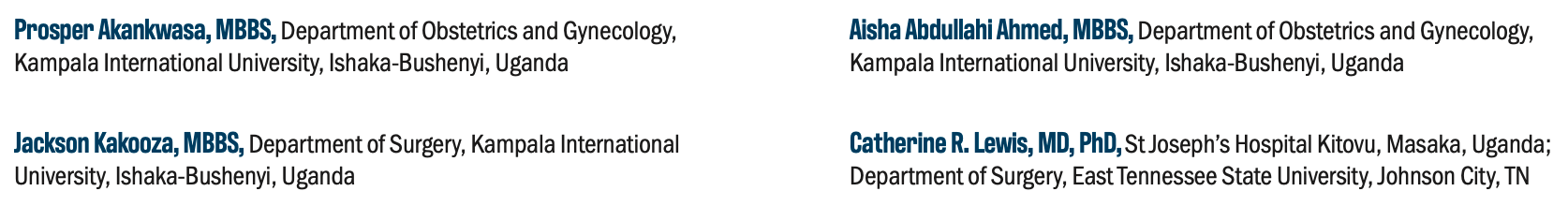

Granulosa cell tumor (GCT) is a rare, hormonally active sex cord-stromal tumor (SCST) of the ovary, accounting for approximately 2% to 5% of all ovarian malignancies1,2 and nearly 70% of SCSTs,3 making it a clinically significant but uncommon subtype within the spectrum of ovarian cancers. GCT affects both pediatric and adult populations and typically presents as a large abdominal or pelvic mass, often asymptomatic but occasionally associated with signs of hyperestrogenism, such as abnormal uterine bleeding.4 Diagnosis relies on histological examination, characterized by monomorphic cells with nuclear grooves with Call-Exner bodies, and immunohistochemical positivity for markers such as inhibin, calretinin, and anti-Mullerian hormone, with inhibin being the most specific.5,6 GCT may appear cystic, solid, or mixed, with histological variability including atypical cells.6

Prognosis is generally favorable, with 10-year survival rates exceeding 90% for stage I disease, though initial tumor stage significantly influences outcomes.7 Late recurrence, occurring 10 or more years post treatment, is a hallmark of GCT,3,8,9 with common sites including the pelvis10 and peritoneum.11 Hepatic metastasis is exceedingly rare, and only 5% to 6% of cases are known to recur in the liver.12 We present a rare instance of GCT recurrence with hepatic metastasis 15 years after initial diagnosis, highlighting the importance of prolonged surveillance in these patients.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old woman with obesity presented with a 1-month history of right upper quadrant abdominal pain. The pain was described as constant and gradually increasing in intensity over 1 month. The patient had a history of a T1aN0M0 stage IA right ovarian GCT diagnosed 15 years prior (Figure 1). She underwent total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), omentectomy, and adjuvant chemotherapy. No routine follow-up was conducted post treatment.

FIGURE 1. Histopathology of Initial Diagnosis 15 Years Ago.

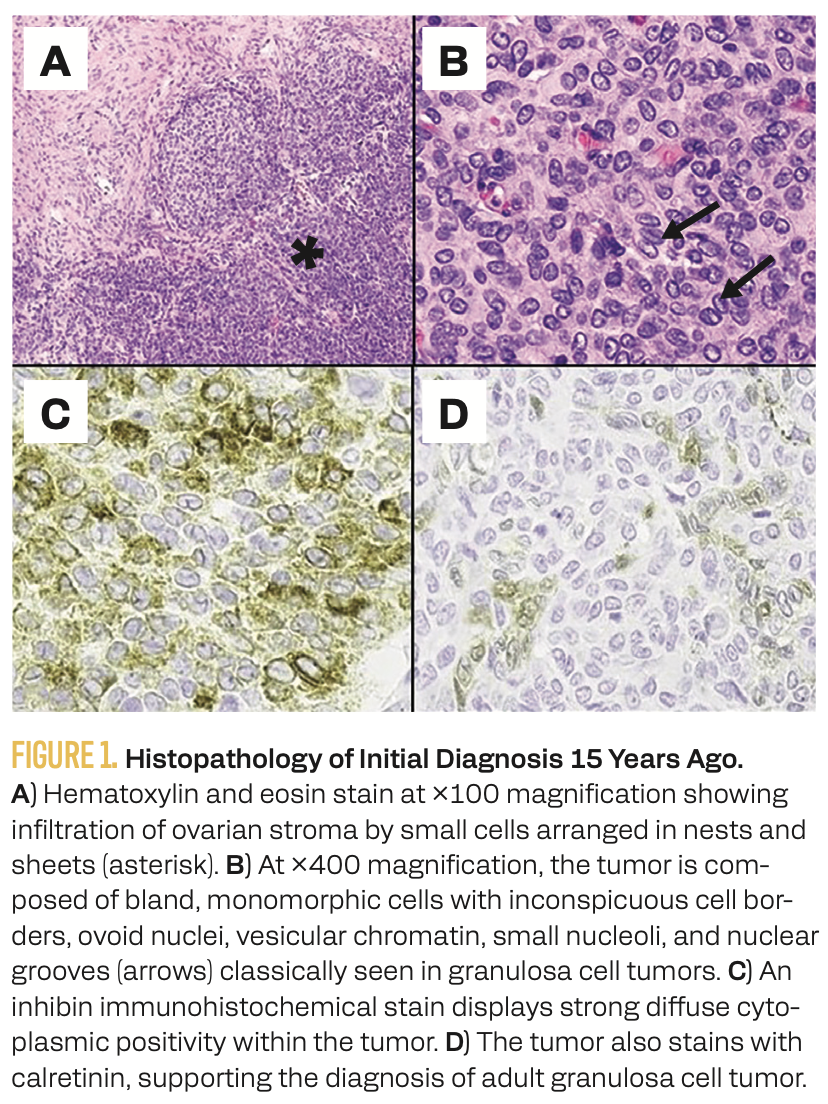

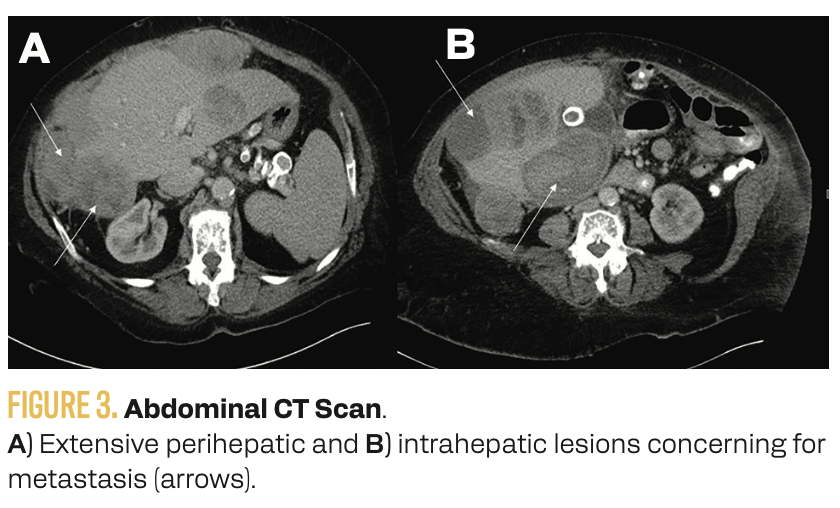

On physical examination, a palpable mass was noted in the midabdomen, extending to the right upper quadrant. Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were unremarkable. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a solid mass with cystic lesions within the liver (Figure 2). An abdominal CT scan demonstrated extensive perihepatic and intrahepatic lesions suggestive of metastasis (Figure 3). A colonoscopy showed only diverticular disease, and a bilateral screening mammogram result was normal.

FIGURE 2. Abdominal Ultrasound.

FIGURE 3. Abdominal CT Scan.

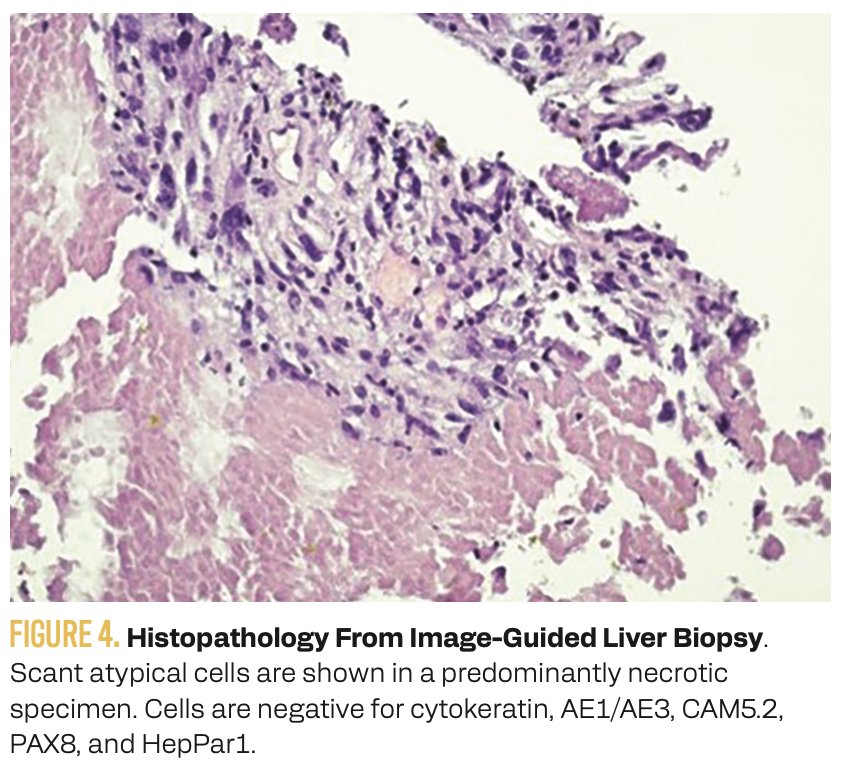

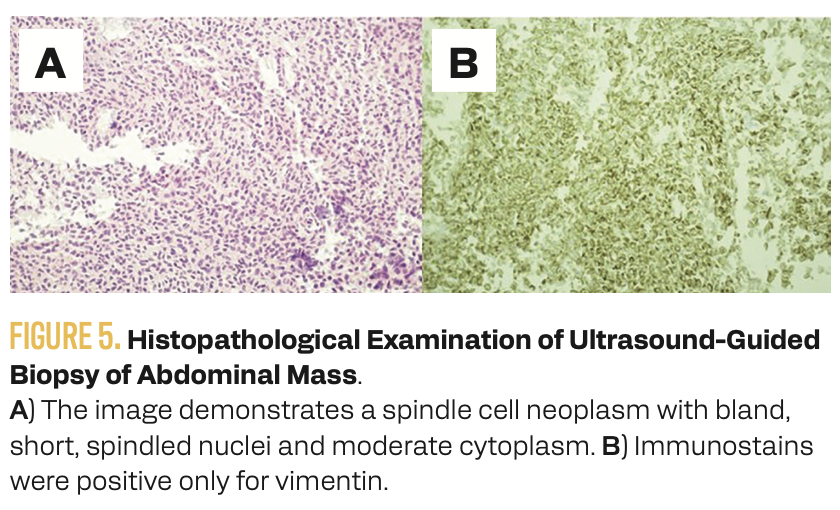

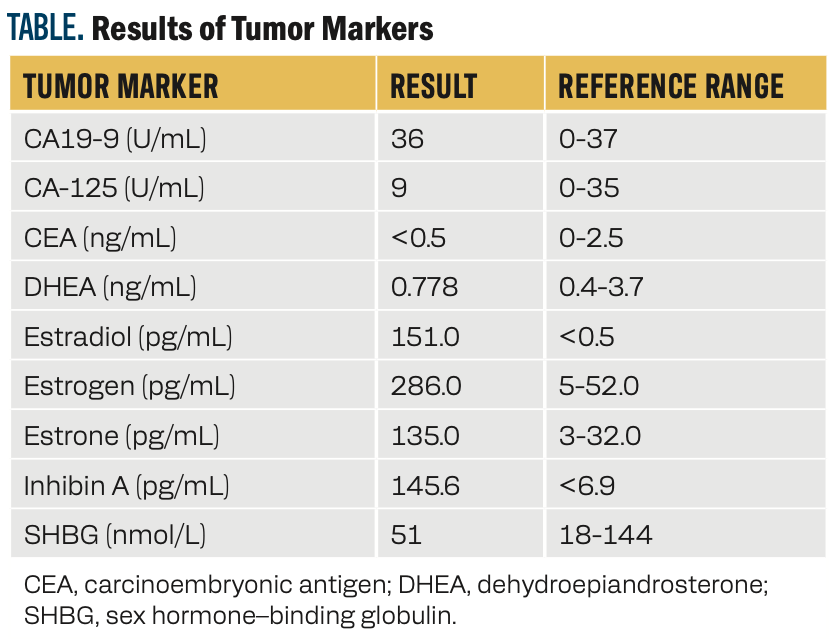

A CT-guided core needle biopsy of the liver and an ultrasound-guided biopsy of an adjacent abdominal mass were performed. Histopathology of the liver specimen demonstrated abundant necrosis with few atypical cells, negative for CKAE1, CKAE3, CAM5.2, PAX8, and HepPar1 (Figure 4). Histopathology of the abdominal mass revealed a spindle cell neoplasm with extensive degeneration, positive for vimentin but negative for cytokeratin, CKAE1, CKAE3, CAM5.2, PAX8, CD45, CD117, CD34, podoplanin, WT1, MART-1, S100, SOX-10, HepPar1, desmin, MSA, and inhibin (Figure 5). These results were deemed inconclusive. Further laboratory evaluation of tumor markers is shown in the Table.

FIGURE 4. Histopathology From Image-Guided Liver Biopsy.

FIGURE 5. Histopathological Examination of Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy of Abdominal Mass.

TABLE. Results of Tumor Markers

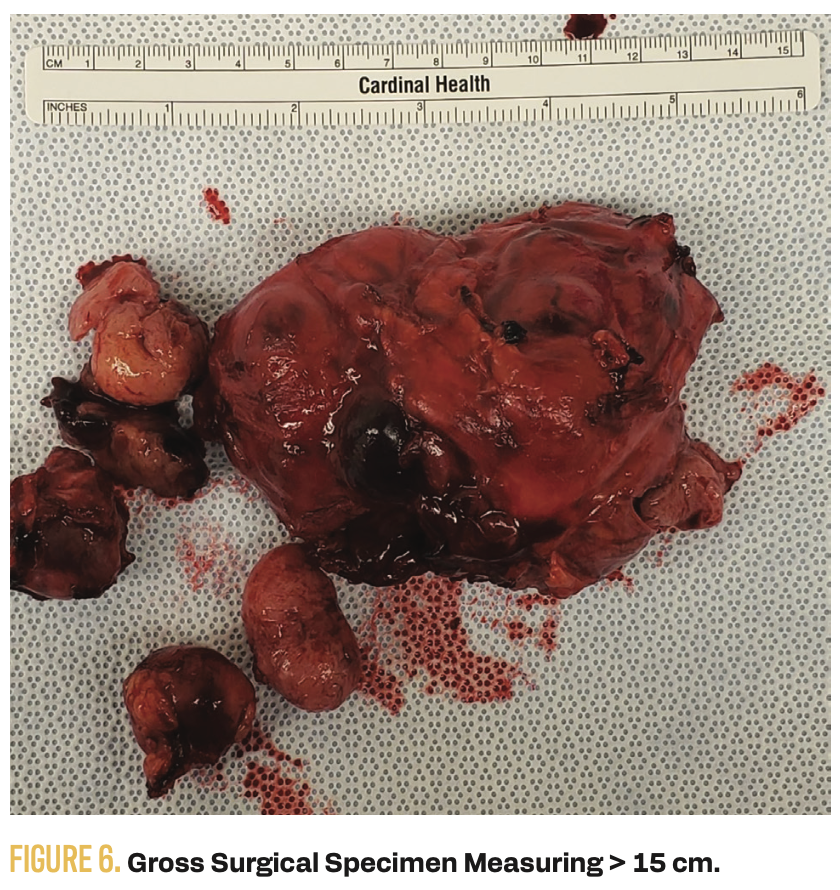

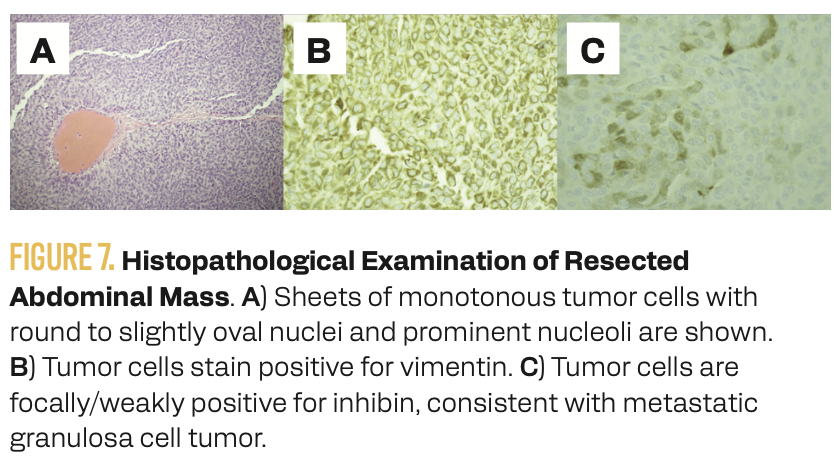

Inconclusive results of the 2 separate biopsies warranted an excisional biopsy. An exploratory laparotomy revealed moderate ascites, a midabdominal mass greater than 15 cm (Figure 6), and extensive disease involving the left liver lobe, right liver lobe, and right lateral abdominal wall. Ascitic fluid was sent for cytology, and complete debulking of the abdominal wall and peritoneum was performed. Cytological examination of ascitic fluid showed atypical cells. The resected specimen was positive for vimentin and calretinin, and focally/weakly positive for inhibin, but negative for CAM5.2, AE1/AE3, CD117, S100, MART-1, WT1, D2-40, CD34, CD10, muscle-specific actin, and desmin (Figure 7).

FIGURE 6. Gross Surgical Specimen Measuring > 15 cm.

FIGURE 7. Histopathological Examination of Resected Abdominal Mass

Based on the patient’s history, histopathology, and immunohistochemical findings, the final diagnosis of metastatic GCT was made. The patient recovered well post laparotomy and was discharged on postoperative day 5 to a skilled nursing facility. Palliative radiation therapy was recommended pending MRI brain and PET-CT results, with referral to medical and radiation oncology. Three weeks post discharge, the patient presented with right arm swelling. A right upper extremity ultrasound confirmed a deep venous thrombosis (DVT), and rivaroxaban 20 mg daily was initiated. One week later, the patient died.

Discussion

GCT was first described by Rokitansky in 1855,6 and it has an annual incidence of 0.6 to 1.0 per 100,000 women.1,2 As an SCST, GCT is distinguished by its hormonal activity, frequently secreting estrogen, which may manifest as abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial hyperplasia, or other hyperestrogenic symptoms.4,13 The tumor also secretes inhibin, making it a useful tumor marker for surveillance.4 Histologically, GCT is characterized by monomorphic cells with ovoid nuclei, vesicular chromatin, small nucleoli, and distinctive nuclear grooves (“coffee bean” nuclei), typically arranged in nests, sheets, or trabecular patterns. Call-Exner bodies are pathognomonic for GCT,6,9 and their absence may be associated with a worse prognosis.6 Immunohistochemical staining is pivotal for diagnosis, with inhibin and calretinin being highly specific markers, while tumors are negative for EMA, CD10, CK7, and CK20.6,9-11 Initially, the image-guided biopsy specimen in our patient was negative for inhibin. However, final immunohistochemical analysis of the resected specimen demonstrated positivity for calretinin and inhibin, with negativity for CD10, consistent with a diagnosis of GCT.

Surgical resection, typically involving TAH and BSO, is the cornerstone of treatment for early-stage GCT.3,10,11,13 Fertility-sparing surgery with unilateral oophorectomy may be feasible in young patients with early disease.10,11,13 Platinum-based chemotherapy is indicated for advanced-stage disease or high-risk stage I tumors.2,3,7 The role of radiation in the management of GCT is not well-defined. However, it may be reserved for advanced stages or recurrence.7,10,11

GCT is notorious for its propensity for late recurrence, often occurring 10 years post treatment, though recurrences as late as 40 years have been documented.14-16 The pelvis and peritoneum are the most common sites of recurrence, concerning for missed peritoneal disease at initial surgery.11 Hepatic metastases, however, are exceptionally rare, occurring in only 5% to 6% of cases.17,18 The longest reported relapse-free survival with hepatic recurrence is reported at 27 years.17,19 Hepatic metastases in one segment are also rare, as the tumors are often large and involve a wide area of liver parenchyma.17 Recurrence occurs in up to 35% of patients,17,18 and the risk of recurrence is influenced by factors such as higher tumor stage at diagnosis, increased mitotic activity, or tumor size greater than 10 to 15 cm.6,7 Our patient had hepatic recurrence 15 years after initial treatment. Long-term surveillance with clinical evaluation, tumor marker monitoring, and imaging is essential due to the risk of late relapse.

The extensive hepatic involvement in this case precluded curative resection, necessitating palliative chemotherapy and radiation, consistent with treatment strategies for advanced or unresectable GCT recurrences.7,10,11 Radiofrequency ablation may be an alternative for extensive hepatic disease. In contrast, cases with limited hepatic metastases may benefit from debulking surgery, demonstrating improvement in survival and quality of life.17 The patient’s rapid clinical decline, marked by a DVT and death within a month post discharge, highlights the aggressive behavior of late-stage GCT recurrence and the need for routine surveillance.

Conclusion

GCT is a treatable malignancy, particularly in early stages, but its propensity for late recurrence and rare metastasis, as seen in this case with hepatic recurrence 15 years post diagnosis, necessitates lifelong surveillance. This case emphasizes the necessity of lifelong surveillance, including regular clinical assessments, tumor marker monitoring, and imaging, to facilitate early intervention and potentially improve outcomes in patients with GCT.

Corresponding author

Catherine Lewis, MD, PhD

Department of Surgery

PO Box 70575

Johnson City, TN 37614

Phone: +1-678-427-9329

Fax: +1-855-275-8432

Email: cathymdphd@gmail.com

References

- Roze JF, van Meurs HS, Monroe GR, et al. [18F]FDG and [18F]FES positron emission tomography for disease monitoring and assessment of anti-hormonal treatment eligibility in granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. Oncotarget. 2021;12(7):665-673. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.27925

- Meisel JL, Hyman DM, Jotwani A, et al. The role of systemic chemotherapy in the management of granulosa cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(3):505-511. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.12.026

- Li J, Chu R, Chen Z, et al. Progress in the management of ovarian granulosa cell tumor: a review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(10):1771-1778. doi:10.1111/aogs.14189

- Birbas E, Kanavos T, Gkrozou F, Skentou C, Daniilidis A, Vatopoulou A. Ovarian masses in children and adolescents: a review of the literature with emphasis on the diagnostic approach. Children (Basel). 2023;10(7):1114. doi:10.3390/children10071114

- van der Vorst MJDL, Bleeker MCG, Boven E. Unusual presentation of granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29): e554-e556. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.29.6905

- Guleria P, Kumar L, Kumar S, et al. A clinicopathological study of granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: can morphology predict prognosis? Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2020;63(1):53-59. doi:10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_403_19

- Khosla D, Dimri K, Pandey AK, Mahajan R, Trehan R. Ovarian granulosa cell tumor: clinical features, treatment, outcome, and prognostic factors. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6(3):133-138. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.128475

- Sehouli J, Drescher FS, Mustea A, et al. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: 10 years follow-up data of 65 patients. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(2C):1223-1229.

- Koukourakis GV, Kouloulias VE, Koukourakis MJ, et al. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: tumor review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2008;7(3):204-215. doi:10.1177/1534735408322845

- Schumer ST, Cannistra SA. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1180-1189. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.10.019

- Kottarathil VD, Antony MA, Nair IR, Pavithran K. Recent advances in granulosa cell tumor ovary: a review. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013;4(1):37-47. doi:10.1007/s13193-012-0201-z

- Madhuri TK, Butler-Manuel S, Karanjia N, Tailor A. Liver resection for metastases arising from recurrent granulosa cell tumour of the ovary--a case series. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010;31(3):342-344.

- Dridi M, Chraiet N, Batti R, et al. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: a retrospective study of 31 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Surg Oncol. 2018;2018:4547892. doi:10.1155/2018/4547892

- East N, Alobaid A, Goffin F, Ouallouche K, Gauthier P. Granulosa cell tumour: a recurrence 40 years after initial diagnosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27(4):363-364. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)30464-9

- Singh-Ranger G, Sharp A, Crinnion JN. Recurrence of granulosa cell tumour after thirty years with small bowel obstruction. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2004;1(1):4. doi:10.1186/1477-7800-1-4

- Abaid LN, Mosquera-Caro M, Kankus RC, Goldstein BH. Extraordinarily prolonged disease recurrence in a granulosa cell tumor patient. Case Rep Oncol. 2010;3(3):310-314. doi:10.1159/000320740

- Yu S, Zhou X, Hou B, Tang B, Hu J, He S. Metastasis of the liver with a granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(2):816-818. doi:10.3892/ol.2014.2784

- Fujita F, Eguchi S, Takatsuki M, et al. A recurrent granulosa cell tumor of the ovary 25 years after the initial diagnosis: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;12:7-10. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.05.004

- Laski D, Topolewski P, Zadkowski S, Guzik P, Drobinska A, Remiszewski P. Extremely late recurrence of adult granulosa cell tumor in the retroperitoneal space 27 years after surgery manifesting as a liver tumor. Ginekol Pol. 2024;95(7):586-587. doi:10.5603/gpl.99959