Level of Scientific Evidence Underlying the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hematologic Malignancies: Are We Moving Forward?

The level of scientific evidence in National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for malignant hematological conditions haven’t been recently investigated. Herein, investigators describe the distribution of categories of evidence and consensus among the 10 most common hematologic malignancies with regard to recommendations for staging, initial and salvage therapy, and surveillance.

Chengappa is from the Department of Medicine at Nazareth Hospital in Philadelphia, PA.

Desai is from the Department of Hematology and Oncology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN.

Go is from the Department of Hematology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN.

Poonacha is from the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Minneapolis, MN.

ABSTRACT

Background: The level of scientific evidence in National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for malignant hematological conditions haven’t been recently investigated. We describe the distribution of categories of evidence and consensus (EC) among the 10 most common hematologic malignancies with regard to recommendations for staging, initial and salvage therapy, and surveillance.

Methods: We reviewed the level of evidence for the 10 most common hematological malignancies by incidence in the United States as of 2020. The NCCN definitions for EC are: category 1, high level of evidence, such as randomized controlled trials, with uniform consensus; category 2A, lower level of evidence with uniform consensus; category 2B, lower level of evidence without a uniform consensus but with no major disagreement; and category 3, any level of evidence but with major disagreement. We compared our results with previously published results from 2011.

Results: Of 1353 recommendations, 5%, 91%, 4%, and 1% fell into EC categories 1, 2A, 2B, and 3, respectively, while in 2011 the comparable percentages were 3%, 93%, 4%, and 0%, respectively. Recommendations with category 1 EC were found in all guidelines, except for Burkitt lymphoma. Of all therapeutic recommendations, 6.3% were category 1 EC, with the majority of these (56.4%) pertaining to initial therapy. Guidelines with highest proportions of therapeutic recommendations with category 1 EC were multiple myeloma (12.4%), chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (6.9%), and acute myeloid leukemia (5.6%).

Conclusions: Recommendations in the 2020 NCCN guidelines are largely developed from lower levels of evidence but with uniform expert opinion, underscoring the urgent need and available opportunities to expand the current evidence base in malignant hematological disorders.

Oncology (Williston Park). 2021;35(7):390-396.

DOI: 10.46883/ONC.2021.3507.390

Introduction

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is an interdisciplinary approach that integrates clinical experience and patient values with the best available research information to make clinical decisions for individual patients. Health care providers always seek to base their decisions on the best available evidence. EBM aims for the ideal that health care professionals should make “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence” in their everyday practice.1

EBM has improved the practice of medicine by developing methods and techniques for generating systemic reviews and clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).2 The Institute of Medicine defines CPG as “statements that include recommendations, intended to optimize patient care, that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.”3,4 CPGs are an essential tool to translate evidence-based medicine into practice and have an emerging role in national policy to guide reimbursement and to serve as the standard of care in medical malpractice cases.3 Within hematology, several organizations provide CPGs for medical practitioners as practice guidance, including the American Society of Hematology (ASH), European Hematology Association, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). In the United States, NCCN guidelines are the most comprehensive standard for clinical care in malignant hematology, and they are widely used by clinicians and payers.

The NCCN is a not-for-profit alliance of 31 leading US cancer centers. designated as National Cancer Institutes (NCI). The organization has engaged in the development of clinical practice guidelines for the past years, utilizing the best contemporary evidence and expert consensus.5 Currently, 73NCCN guidelines for different forms of cancer cover cancer detection, prevention and risk reduction, work-up and diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care. These guidelines have become important documents for guiding clinical practice, insurance reimbursements, and quality improvement initiatives around the globe.6 The guidelines are developed and updated by 60 individual panels comprised of more than 1520 members who are both clinicians and researchers. These guidelines are updated at least annually.7

The authors of a review of the 2011 NCCN clinical practice guidelines found that only 3% of the recommendations were based on high levels of evidence.8 Given that the vast majority of guidelines in malignant hematology were based on lower levels of evidence, a need was noted for increased comparative effectiveness research and compliance studies within the field of hematology. However, the categories of evidence and consensus in NCCN guidelines for malignant hematological conditions have not been recently investigated. In this study, we aimed to describe the distribution of categories of evidence and consensus (EC) among the 10 most common hematologic malignancies with regard to recommendations for staging, initial and salvage therapy, and surveillance. We also sought to evaluate the changes in level of evidence between the most recent NCCN guidelines, from 2020, and those published in 2011.

Methods

From the NCCN website, we obtained the latest versions (as of July 2020) of CPGs for relevant hematological malignancies9: acute myeloid leukemia (AML), multiple myeloma (MM), Hodgkin lymphoma (both adult and adolescent/young adult), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), AIDS-related B-cell lymphoma, and Burkitt lymphoma. Only comprehensive guidelines were included in this study; NCCN evidence blocks, quick guide, NCCN framework and guidelines for patients were not included.9-14

We reviewed the number of recommendations included in the CPGs for each malignancy and the level of evidence associated with each recommendation.15,16 We abstracted the recommendations after carefully reviewing the content within each guideline document and the displayed text within the graphical algorithms. We enumerated the EC categories for each of the guidelines according to the following 4 major areas of recommendations: staging, initial treatment, salvage treatment, and surveillance.

The NCCN definitions for various EC categories are as follows: (A) category 1: high-level evidence with uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate; (B) category 2A: lower-level evidence with uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate; (C) category 2B: lower-level evidence without a uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate but with no major disagreement; and (D) category 3: any level of evidence but with major disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.9 Data obtained from the current guidelines as of July 2020 were compared with previously published results from November 2011.8

Results

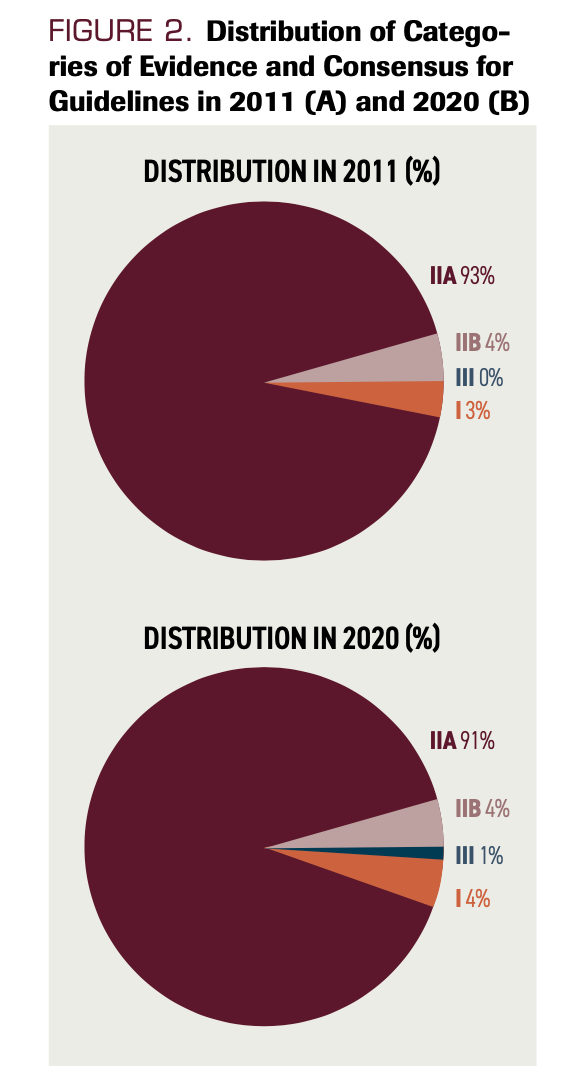

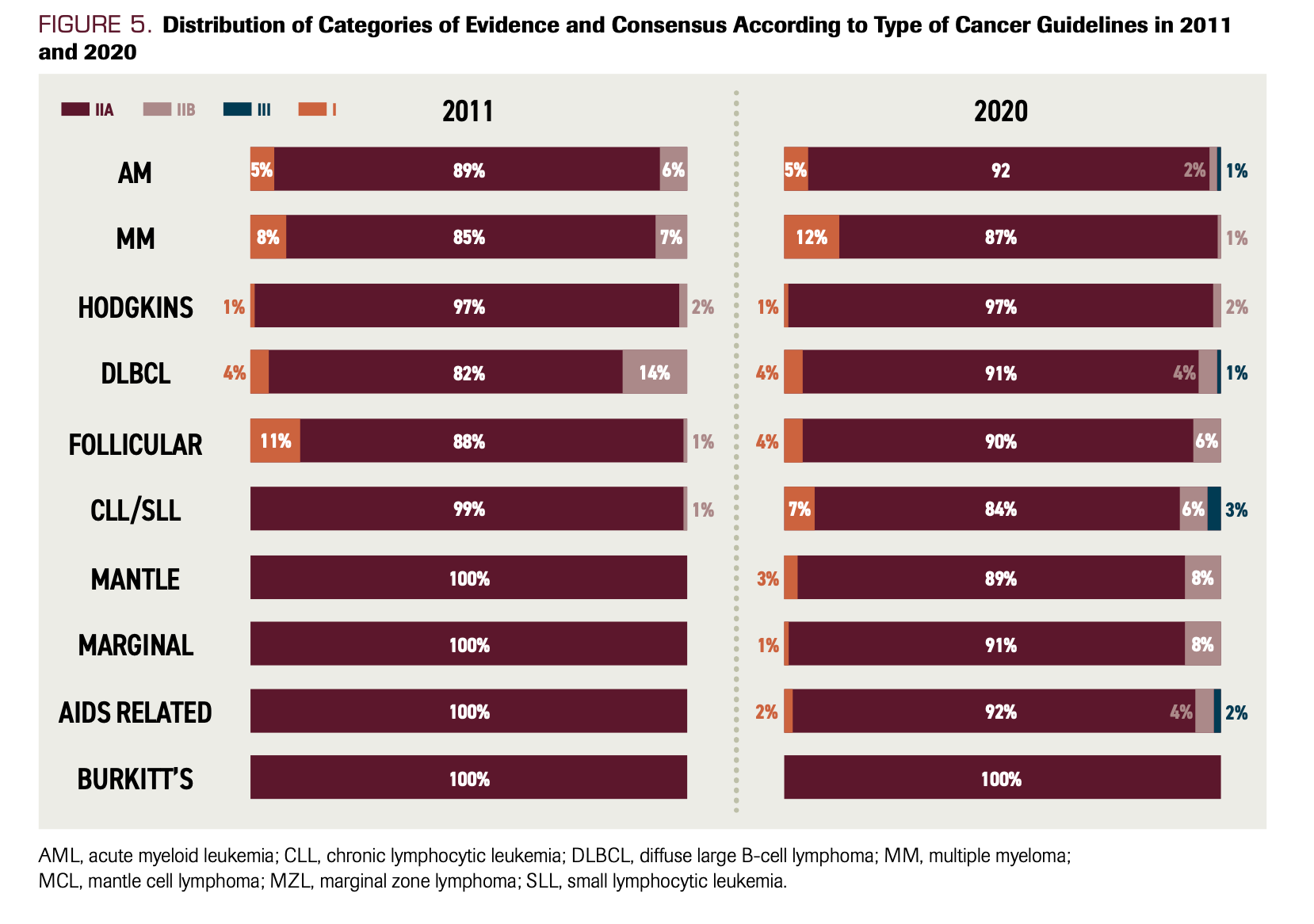

The ten July 2020 guidelines included a total of 1353 recommendations. Of the 1353 recommendations, 5%, 91%, 4%, and 1% fell into categories 1, 2A, 2B, and 3 EC, respectively; the comparable percentages in November 2011 were 3%, 93%, 4%, and 0%, respectively. Recommendations with category 1 EC were for MM (12%), CLL/SLL (7%), AML (5%), follicular lymphoma (4%), DLBCL (4%), MCL (3%), Hodgkin lymphoma (2%), AIDS-related B-cell lymphoma (2%), and MZL (1%). No category 1 recommendations were noted in Burkitt lymphoma. Of all 980 therapeutic recommendations, 6.3% were in category 1 EC; the majority of these, 56.4%, pertained to initial therapy. MM (12.4%), CLL/SLL (6.9%), and AML (5.6%) guidelines had the highest proportions of category 1 therapeutic recommendations. No category 1 recommendations were made for staging or surveillance guidelines.

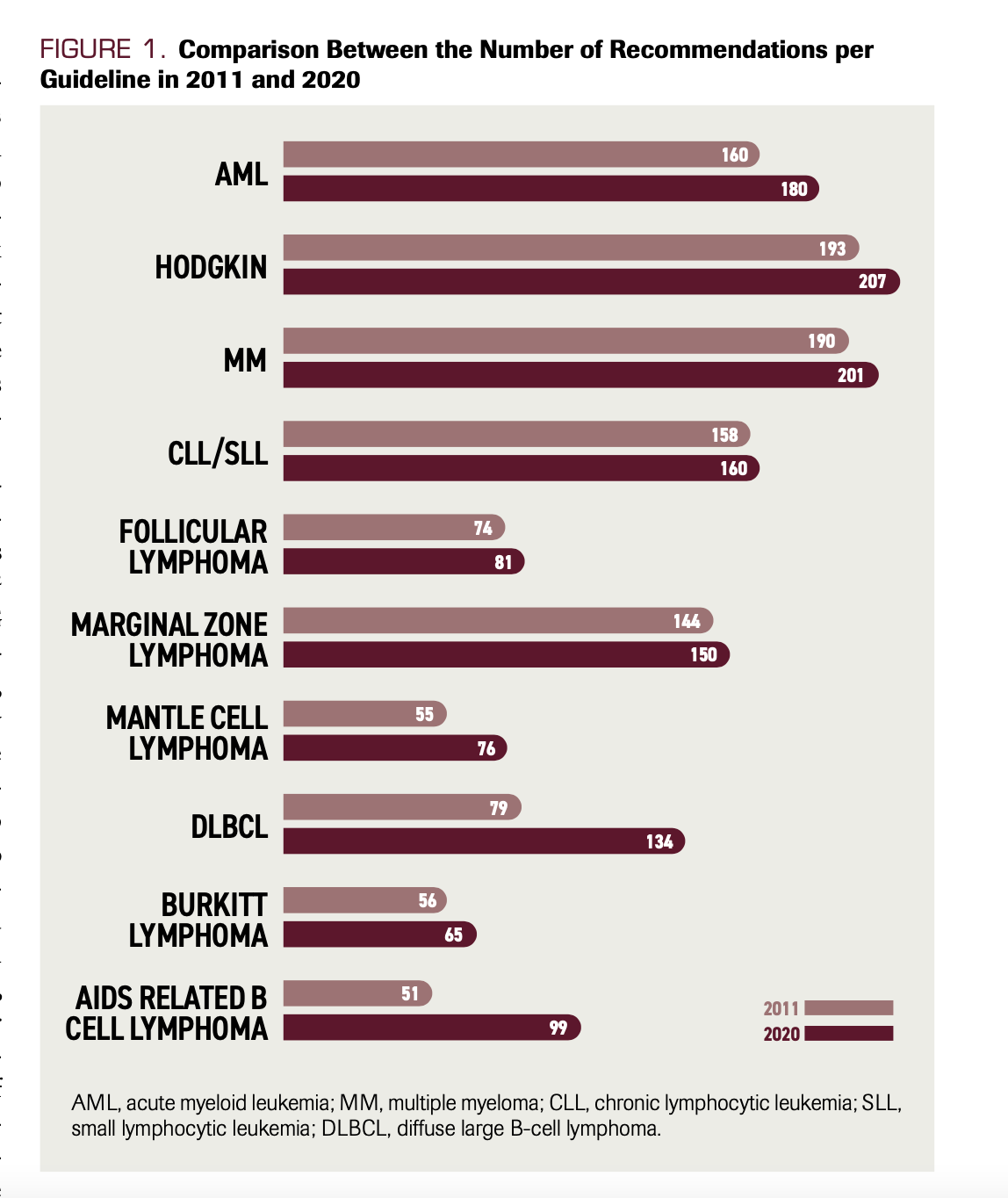

In comparison with the guidelines studied in 2011, the total number of recommendations in 2020 increased by 16.6%, rising from 1160 to 1353 (Figure 1). Hodgkin lymphoma continued to have the most recommendations (n = 207). AIDS-related B-cell lymphoma had the least recommendations in 2011 (n = 51), whereas in 2020, Burkitt lymphoma had the least (n = 65) . The majority of recommendations both in 2011 and 2020 were based on category 2A EC. While a small fraction of recommendations were based on category 1 EC, that percentage did improve from 3% to 4% (Figure 2). Majority of the recommendations in this 1% increase were in the therapeutic category.

FIGURE 1. Comparison Between the Number of Recommendations per Guideline in 2011 and 2020

FIGURE 2. Distribution of Catego- ries of Evidence and Consensus for Guidelines in 2011 (A) and 2020 (B)

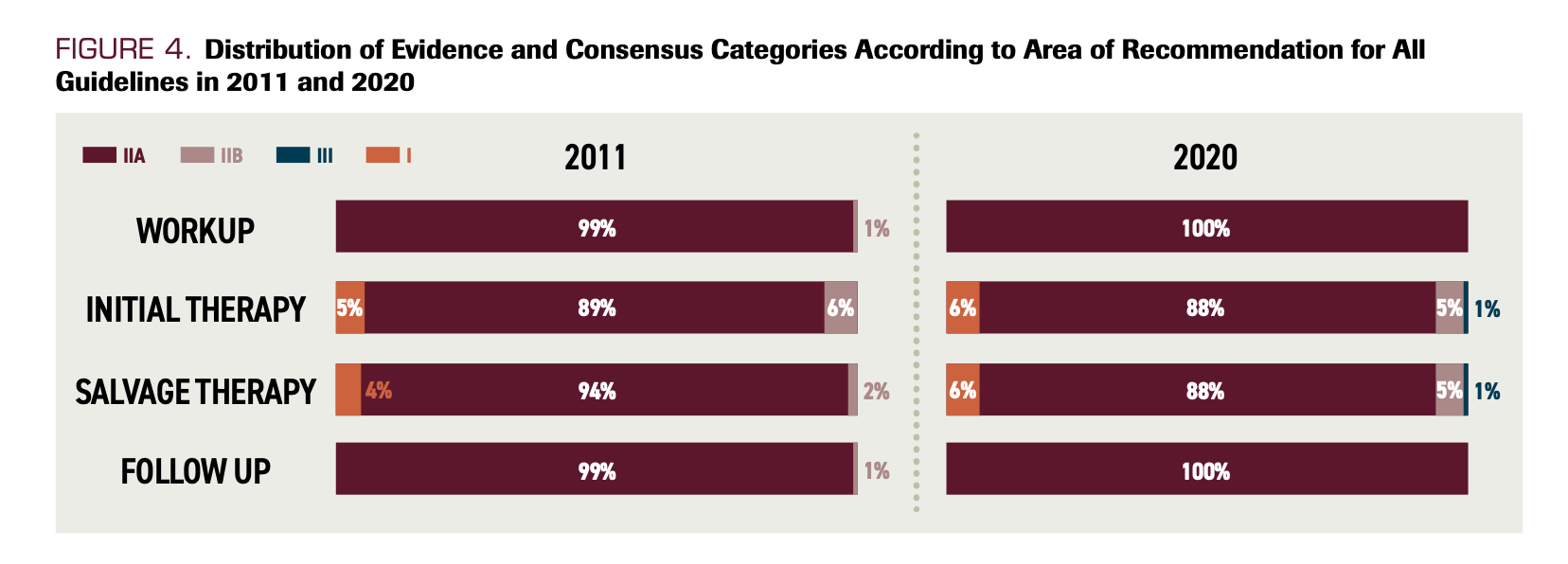

Figure 4 shows the similarity of the distribution of recommendations among the major areas in both years studied. The distribution of evidence among the different types of recommendations demonstrated that 5% of initial therapy recommendations and 4% of salvage therapy recommendations had category 1 EC in 2011; those figures both increased to 6% in 2020, suggesting improved evidence in the therapeutic recommendations section of the guidelines (Figure 4). Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of categories of evidence and consensus for each CPG. Nearly all recommendations on staging and surveillance were based on category 2A EC, with none having category 1 EC, both in 2011 and 2020.

FIGURE 4. Distribution of Evidence and Consensus Categories According to Area of Recommendation for All Guidelines in 2011 and 2020

FIGURE 5. Distribution of Categories of Evidence and Consensus According to Type of Cancer Guidelines in 2011 and 2020

In 2011, the highest proportions of category 1 recommendations were found in the follicular lymphoma guidelines (11%). No category 1 recommendations were found for CLL/SLL,

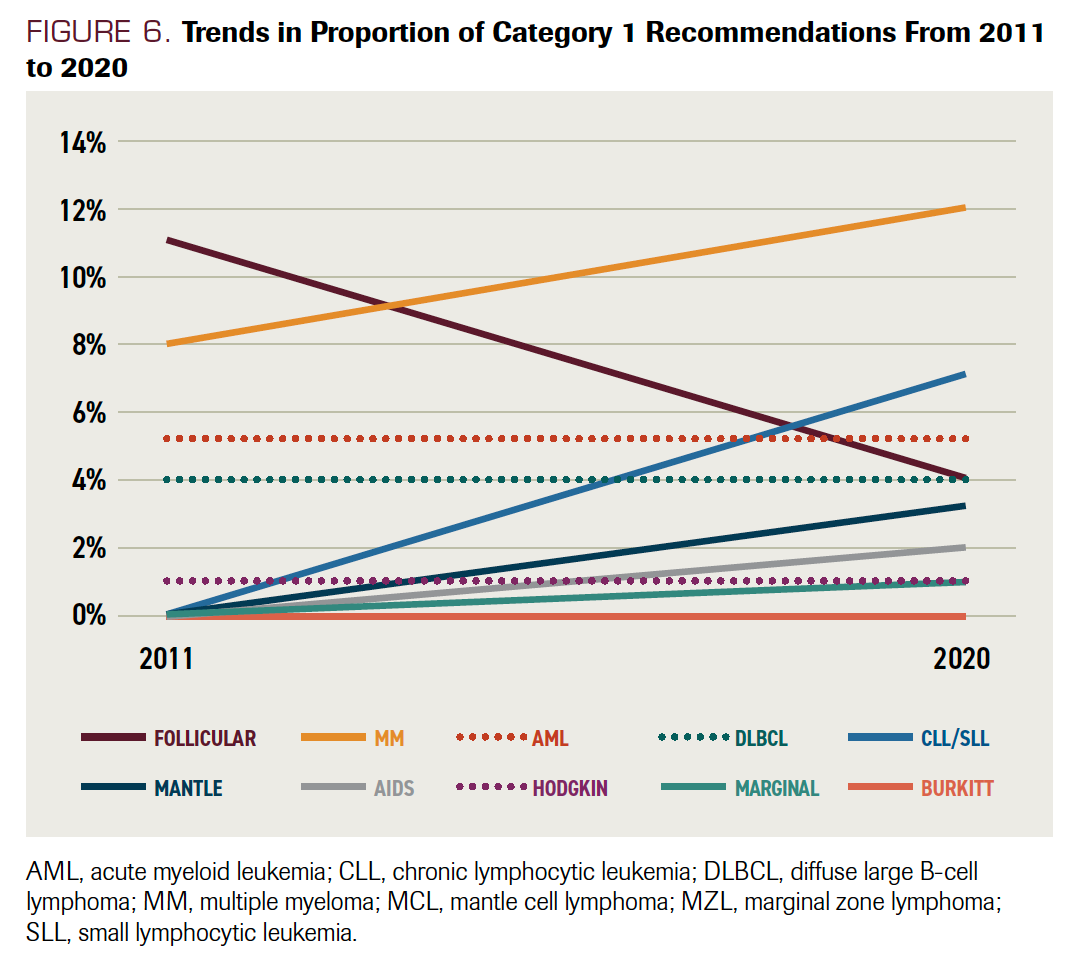

MZL, MCL, AIDS-related B-cell lymphoma, or Burkitt lymphoma. In 2020, MM (12%) had the highest proportion of category 1 recommendations. Between 2011 and 2020 (Figure 6), the proportion of category 1 recommendations increased in MM, CLL/SLL, MCL, MZL, and AIDS-related B-cell lymphoma; CLL/SLL had a significant increase in category 1 recommendations from 0% (2011)to 7% (2020). Burkitt lymphoma did not have any category 2 recommendations. Category 1 recommendations for follicular lymphoma had a downward trend from 11% (2011) to 4% (2020).

FIGURE 6. Trends in Proportion of Category 1 Recommendations From 2011 to 2020

Discussion

Our study describes the distribution of EC categories among the 10 most common hematologic malignancies with regard to recommendations for staging, initial and salvage therapy, and surveillance based on the latest data from 2020 in comparison with previously published data from 2011. Overall, we found that the total number of recommendations increased from 2011 to 2020 by 16.6%, with less than 10% of recommendations based on high-level evidence, characterized as category 1. The proportion of category 1 recommendations increased in all CPGs except follicular cell lymphoma and Burkitt‘s lymphoma. In fact, follicular cell lymphoma had a decrease in category 1 recommendations.No category 1 EC recommendations were found in screening or surveillance. Despite the increase in the total number of recommendations, the distribution of different categories of EC recommendations were largely similar to those of 2011.

Over the past 25 years, the NCCN has evolved its CPGs, and it currently has 73 CPGs that are developed and updated by 60 individual panels, composed of more than 1520 clinicians and oncology researchers from 31 NCCN member institutions.17 NCCN releases CPGs, developed as algorithms or flowcharts, that cover more than 97% of all cancers affecting patients in United States and are updated several times per year. The recommendations and updates are based on the best and latest available scientific evidence integrated with expert judgment of leading clinicians, and they are intended to assist all individuals who impact decision-making in cancer care, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, payers, patients, and families. NCCN CPGs are the most widely used CPGs for cancer care in the world and have been translated into more than 70 languages.

The NCCN guideline development panel comprises the NCCN guidelines steering committee, panels specific to each of the guidelines, and the NCCN headquarters team, which supports the panels and the activities of guideline development. Each NCCN guidelines panel consists of a panel chair, vice-chair (or co-chair), and a group of representatives from the NCCN member institutions. The NCCN guideline development process consists of annual institutional review of the guidelines by the experts at the NCCN member institutions. They follow an elaborate protocol, ultimately resulting in voting if the discussion calls for a change in guidelines. The panel chair and members then develop the specific recommendations as algorithms. The scientific rationale and clinical evidence supporting the recommendations outlined in the algorithms are provided in the discussion sections.9

Per the NCCN, “the level of evidence depends upon the following factors, which are considered during the deliberation process by the panel: quality of data (eg, trial design and how the results/observations were derived [randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-RCTs,

meta-analyses or systematic reviews, clinical case reports, case series]), quantity of data (eg, number of trials, size of trials, clinical observations only), and consistency of data (eg, similar or conflicting results across available studies or observations).” The determination of level of evidence is subjective and is based on the panel’s decision, depending on the quality, quantity, and consistency of the available data. The degree of consensus among the panelists is based on the percentage of panel votes.

Per NCCN’s policy on development and update of guidelines, “for uniform NCCN consensus defined in category 1 and category 2A, a majority panel vote of at least 85% is required. For the “NCCN consensus” defined in category 2B, a panel vote of at least 50% (but less than 85%) is required. Lastly, for recommendations where there is strong panel disagreement regardless of the quality of the evidence, NCCN requires a panel vote of at least 25% to include and designate a recommendation as category 3.” The NCCN guideline document specifies that when categories are not explicitly mentioned within the guidelines, the default designation for such recommendation is category 2A.

Some of the limitations of NCCN guideline development process are that:

- the literature search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction are not described in detail;

- in the current NCCN definition of categories of EC, it seems that the level of evidence is equated with the quality of evidence. High-level evidence (from RCTs) may be of low quality if serious study limitations and biases are present. Conversely, lower-level evidence (observational studies or phase 2 trials) may be of high quality if they show consistent and a large magnitude of treatment effect; and

- the panel decisions on the quality of evidence are not separated from the strength of recommendation. High-quality evidence may be worthy of only a weak recommendation if uncertainty or variability exists in terms of risks and benefits or personal values and preferences. On the contrary, strong recommendations may arise from lower-quality evidence.

Over the past 2 decades the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group has developed a common, sensible, and transparent approach to grading quality (or certainty) of evidence and strength of recommendations.17 It quantifies the strength of recommendations taking into account the estimate of effect of an intervention; the design, execution, consistency, precision, and reporting bias of studies; the patient health benefits vs harms; and the health system costs.18 Many international organizations provide input into the development of the GRADE approach, which is now considered the standard in guideline development. Interestingly, NCCN and other major cancer organizations such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology and Cancer Care Ontario have not adopted GRADE.However, some of the guidelines developed by ASH were based on GRADE.More recently, the European Society of Medical Oncology has adopted the GRADE system as described in their clinical practice guidelines standard operating procedures. If the GRADE system were used by NCCN, the distribution of EC for each guideline would potentially be different.

The relative lack of high-level evidence is not unique to the recommendations arising from NCCN’s hematological malignancies’ CPG. A similar comparative study of NCCN CPGs for the 10 most common cancers in the United States demonstrated that although the number of recommendations increased between 2010 and 2019, the relative distribution of category of evidence and consensus remained essentially the same.16 Similar studies in cardiology have shown that American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines did not demonstrate any major changes in the level of evidence among CPGs between 2010 and 2019.19 In our study, we found that 5% of the recommendations were based on high levels of evidence, representing a 2% increase in comparison with 2011. It is reassuring that most of the increase in level of evidence was found in recommendations for treatment.

The National Cancer Institute has been proactive in assimilating community-based clinical practices to pursue research in oncology and serve as sites for research trials to improve and boost the evidence base. However, these sites face challenges, partly as a result of emerging science, technology, genomics, and molecular target therapy, but more significantly because of changing health care policies and federal support for research. The entry of the pharmaceutical industry into cancer research and their collaboration with academic institutions have also increased the evidence base for cancer diagnoses and treatment. However, in some cases, financial conflicts of interest (FCOI) and the potentially disparate objectives of pharmaceutical companies and academic groups may limit the companies’ overall contribution. 20 While no study results directly correlate issues of FCOI and their impact on guidelines, a recent study concluded that of all the NCCN guidelines, 46% had of guideline panelists reporting at least 1 episode of FCOI.21 Relatedly, another recent study on trends in industry payments to physicians between 2014 and 2018 showed that physicians receiving total payments of more than $50,000 from the pharmaceutical industry continued to receive similar or greater amounts, perhaps reflecting evolving industry strategy that concentrates payments, for which greater return on investment is anticipated.22

NCCN acknowledges that the quality of existing evidence in cancer research is highly variable. Large, well-designed RCTs may provide high-quality clinical evidence in some tumors and clinical situations. However, much of the clinical evidence available to clinicians is primarily based on data from indirect comparisons among randomized trials, phase 2 or nonrandomized trials, or, in many cases, on limited data from multiple smaller trials, retrospective studies, or clinical observations.23 Notably, only approximately 16% of NCCN recommendations are based on the results of randomized phase 3 trials.24

In situations where high-level evidence does not exist, guidelines are derived from critical evaluation of evidence, integrated with the clinical expertise and consensus of a multidisciplinary panel of cancer specialists, clinical experts, and investigators. The guidelines are updated regularly to ensure their transparency, and a “transparency document” is posted on the NCCN website, detailing changes made to recommendation category or indication of drugs or biologics, a short summary of the panel discussion, and the rationale for the change. In addition, all external submission requests are available for viewing on the NCCN website along with the transparency document.7 One could argue about the subjective nature of recommendations, as multiple options exist for 1 specific presentation. This is because many effective regimens were not compared head-to-head in phase 3 trials. However, this allows individualization of therapy to patients based on comorbidities and other variables. Therefore, the subjective nature may be to the advantage of clinicians when high levels of evidence do not exist.

While creating high-level evidence is not the primary responsibility of NCCN, one way to draw attention to required areas of research is by identifying recommendations that are largely based on lower levels of evidence. The current NCCN guidelines do not differentiate between low levels of evidence and no evidence, but this distinction becomes extremely important to outline areas of unmet need. Furthermore, funding could be prioritized to those areas where further research is critical.

Conclusions

Recommendations in the 2020 NCCN guidelines for hematological malignancies are mostly derived from lower levels of evidence and with expert opinion, which has not changed in over 10 years. While NCCN makes every effort to gather the best existing evidence, multiple challenges exist within health care, particularly cancer care, to generate high-quality evidence. Creating awareness, with emphasis on areas where there is a dearth of high-quality evidence, and prioritization of resources may help improve the level and quality of evidence informing the care that we offer to our patients.

*Authors Have equal contribution

Conflicts of Interest: RSG received travel reimbursement from the NCCN to chair the histiocytic neoplasm clinical practice guidelines panel. The other authors have no disclosures.

Author contributions:

Madhuri Chengappa: Data curation, writing – original draft, formal analysis

Aakash P. Desai: Conceptualization, data curation, investigation methodology, formal analysis, review, and editing

Ronald S. Go: Conceptualization, supervision, review, editing, and validation

Thejaswi K. Poonacha: Conceptualization, supervision, review, editing, and validation

References

1. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine. a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268(17):2420-2425. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032

2. Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet. 2017;390(10092):415-423. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31592-6

3. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines; Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, et al, eds. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Press; 2011:summary. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://bit.ly/2PoaxZA

4. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Field MJ, Lohr KN, eds. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. National Academies Press; 1990.

5. The Complete Library of NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2004.

6. McGivney WT. NCCN guidelines and their impact on coverage policy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(6):625. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2010.0048

7. Development and update of guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2021. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://bit.ly/3dUOxyM

8. Kusuma B, Go RS. Level of scientific evidence underlying recommendations arising from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hematologic Malignancies. Blood. 2011;118(21):509. doi:10.1182/blood.V118.21.509.509

9. NCCN guidelines: treatment by cancer type. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2021. https://bit.ly/32NcnGD

10. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Acute myeloid leukemia, version 4.2020. Accessed April 26, 2021.

11. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Multiple myeloma, version 4.2020. Accessed April 26, 2021,

12. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hodgkin lymphoma, version 2.2020. Accessed April 26, 2021.

13. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. B-cell lymphoma, version 2.2020. Accessed April 26, 2021.

14. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, version 2.2020. Accessed April 26, 2021.

15. Poonacha TK, Go RS. Level of scientific evidence underlying recommendations arising from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29(2):186-191. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.31.6414

16. Desai AP, Go RS, Poonacha TK. Category of evidence and consensus underlying National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines: is there evidence of progress? Int J Cancer. 2021;148(2):429-436. doi:10.1002/ijc.33215

17. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490

18. Pentheroudakis G, Stahel R, Hansen H, Pavlidis N. Heterogeneity in cancer guidelines: should we eradicate or tolerate? Ann Oncol. 2008;19(12):2067-2078. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdn418

19. Fanaroff AC, Califf RM, Windecker S, Smith SC Jr, Lopes RD. Levels of evidence supporting American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines, 2008-2018. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1069-1080. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.1122

20. Shnier A, Lexchin J, Romero M, Brown K. Reporting of financial conflicts of interest in clinical practice guidelines: a case study analysis of guidelines from the Canadian Medical Association Infobase. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(a):383. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1646-5

21. Desai AP, Chengappa M, Go RS, Poonacha TK. Financial conflicts of interest among National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guideline panelists in 2019. Cancer. 2020;126(16):3742-3749. doi:10.1002/cncr.32997

22. Marshall DC, Tarras ES, Rosenzweig K, Korenstein D, Chimonas S. Trends in industry payments to physicians in the United States from 2014 to 2018. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1785-1788. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.11413

23. Boland GM, Chang GJ, Haynes AB, et al. Association between adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines and improved survival in patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(8):1593-1601. doi:10.1002/cncr.27935

24. Wagner J, Marquart J, Ruby J, et al. Frequency and level of evidence used in recommendations by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines beyond approvals of the US Food and Drug Administration: retrospective observational study. BMJ. 2018;360:k668. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k668

Navigating AE Management for Cellular Therapy Across Hematologic Cancers

A panel of clinical pharmacists discussed strategies for mitigating toxicities across different multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia populations.